In terms of taste, the balance of a wine depends primarily on the level of acidity and its tannic structure, but equally on its sweetness and smooth taste. This usually relates to “sucrosity”, a neologism which describes a sweet taste unrelated to sugar. But where does the sweetness that can be found in fine dry white wines come from, since it is not the product of residual sugars as is the case with dessert wines?

In terms of taste, the balance of a wine depends primarily on the level of acidity and its tannic structure, but equally on its sweetness and smooth taste. This usually relates to “sucrosity”, a neologism which describes a sweet taste unrelated to sugar. But where does the sweetness that can be found in fine dry white wines come from, since it is not the product of residual sugars as is the case with dessert wines?

Axel Marchal – who holds a doctorate in wine science from the University of Bordeaux – wrote a thesis a few years ago entitled Recherche sur les bases moléculaires de la saveur sucrée des vins secs [Research on the molecular basis of the sweet taste in dry wines]. This was the fruit of research supervised by the eminent academic Professor Denis Dubourdieu. His conclusions provide an insight into how we perceive this oft-mentioned sweet taste.

The sugary or sweet flavour, which is one of the sensations experienced when tasting a white wine, plays a key role in its balance. It is all the more significant because it satisfies our attraction to and our innate craving for sweetness, identified by tasters during sampling, which can be attributed to our diet in particular.

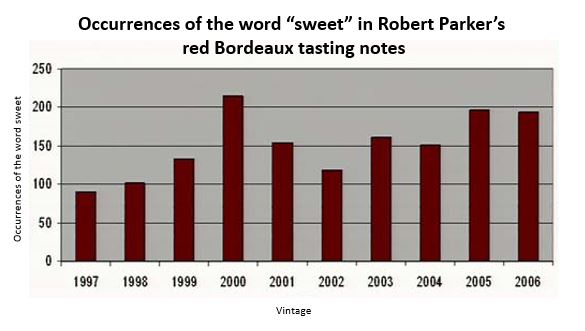

Dessert wines are genuinely sweet as there is a direct link to the presence of residual sugars from grapes (glucose and fructose) which have not been converted by yeasts since fermentation is arrested when the desired alcohol strength is reached. However, in the case of dry white wines, real sugar is present in quantities far below the taste threshold (generally less than 1g/l, whereas the taste threshold for wines is approximately 4-5 g/l). In other words, the sweetness identified in dry white wines does not come from actual sugars. However, this sweetness is unanimously detected by tasters and is even highly desirable. Analysis of the language used in tasting notes by the famous wine taster Robert Parker and a comparison between the occurrence of words from the lexical field of sweetness and his tasting notes, provides a clear correlation with the perceived quality of wines. Wines with the highest occurrence of words expressing sweetness in Parker’s tasting notes are also those he rates most highly. He is not alone in placing a premium on sweetness in white and red wines alike.

The sweetness of wines is therefore a crucial factor in tasting, which is clearly detectable and yet still remains largely overlooked, especially in terms of its molecular origins. It has been proven that certain wine flavours are associated with one or more molecules. Axel Marchal has carried out research specifically to identify molecular factors responsible for the sweet taste of dry white wines.

His research is based on both analytical and sensory techniques, which seems logical, given the nature of the topic. It focuses in particular on the part played by ethanol and glycerol in the sweet taste of dry white wines, and also on the contribution of yeasts and ageing in wooden barrels.

Sweetness has been erroneously attributed to ethanol and glycerol for some time

Ethanol and glycerol are the main compounds in dry white wines (in addition to water, of course). They are formed during alcoholic fermentation. Ethanol (alcohol) is present in dry white wines at a strength of 12 to 14° and glycerol is a natural compound in wine, which is found at concentrations of 3 to 10 ml per litre and gives wine its fatty, easy-drinking characteristics.

Ethanol and glycerol are the main compounds in dry white wines (in addition to water, of course). They are formed during alcoholic fermentation. Ethanol (alcohol) is present in dry white wines at a strength of 12 to 14° and glycerol is a natural compound in wine, which is found at concentrations of 3 to 10 ml per litre and gives wine its fatty, easy-drinking characteristics.

It is frequently suggested that these two compounds play an important role in the sweetness of wines, but research in this area is often contradictory and does not provide clear evidence of a connection. Axel Marchal carried out his own sensory experiment with a panel of experienced tasters and concluded that adding ethanol and glycerol has no significant impact on perception of the sweetness of a wine.

In the final analysis, these two elements have no – or very little – impact on the sweetness of wines. Furthermore, there is no known sweetening agent in wines. Other chemical elements must therefore exist to enhance the sweet taste and we know that experts can detect an increase in sweet flavour after post-fermentation maceration of red wines (extended vatting after alcoholic fermentation so that the wine stays in contact with the must and yeasts) and also after oak ageing.

The role of yeasts and the Hsp12 protein in particular

Winemakers detect an increase in the sweetness of wines after post-fermentation macerations of red wine and the enhanced flavour is therefore naturally associated with yeast autolysis (destruction of yeasts and diffusion of their content in the wine). This suggests that they release compounds which increase sweetness. This observation in relation to red wine can also be extended to white wines which are placed in contact with the lees.

At the end of the fermentation process, wine is placed in contact with the lees (comprising mainly yeasts, grape skins and seeds). During this period, the yeasts break down and self-destruct under the impact of endogenous enzymes, and this is known as yeast autolysis. For white wines, this process takes place during ageing on the lees. Contact with the lees causes multiple physicochemical and organoleptic changes in the wine (which affect our sensory receptors) such as changes in woody flavours, and first and foremost an increase in sweetness. Axel Marchal has in fact proven that the sweetness detected by tasters increases with the quantity of yeasts present during autolysis. This would seem to hold true in particular for a specific protein present in yeasts (the Hsp12 protein), which increases the sweetness of a wine, probably by releasing compounds during autolysis. Moreover, this is the first experiment which proves that there is a connection between a yeast protein and the taste of a wine. The way in which this protein expresses itself depends on temperature, oxidative stress and the concentration of ethanol and glycerol.

The sweetening effect of oak ageing

Similarly, experts note that producing wines in oak barrels (vinification and/or ageing) also changes the sensory properties of wine, enhancing flavour in particular, and notably increasing sweetness. Axel Marchal carried out an experiment with a panel of tasters using different containers (stainless steel vats, new barrels and used barrels) and concluded that the sweetness of wine increased with exposure to wood, as it was more intense in barrels than vats, and tended to decrease as the container got older (the sweetness was more intense when ageing in new barrels). These changes in flavour can be attributed partly to oxydoreduction phenomena (since wood is relatively permeable to oxygen), and also to the extraction of specific compounds which alter the taste characteristics of wine. The study attempted to isolate these volatile and non-volatile compounds in wood.

This research proved that the increase in sweetness was not the result of cognitive bias creating an association between flavours usually found in sweet foods and a perception of sweetness. In other words, the perception of increased sweetness of wine aged in wood was genuine and not merely imagined (through an association of smells and tastes, such as connecting a vanilla scent with a sweet taste because they are usually associated with each other). Sweetness produced by ageing is therefore not associated with volatile compounds in wood (smells), but actually with non-volatile molecules.

The research isolated the wood compounds responsible for the increase in sweetness, which are newly discovered molecules. The more scientifically-minded among you will be interested to know that they have been dubbed quercotriterpenoside I and III. The presence of these sweet-tasting molecules in dry white wines increases with the length of ageing and decreases with barrel age (new barrels contain more of them). This phenomenon can be observed very clearly in brandies, which are aged for a long time and become sweeter.

In the conclusion of his thesis, the author outlines future avenues for more in-depth research in this vast field. He suggests in particular the study of the role of terroirs and grape varieties, which could also be important in explaining the differences in sweetness perceived in dry white wines vinified and aged in an identical manner. The mystery of fine wines and terroirs has not yet been penetrated.

Now that the molecular basis of sweetness in dry white wines no longer holds any secrets for you (or fewer than before, at least) you can slip into a conversation that “The sweetness of a dry white wine comes in part from the Hsp12 protein present in yeasts, as well as quercotriterpenoside I and III molecules found in oak.” That should certainly make an impression!

View Axel Marchal presenting his thesis