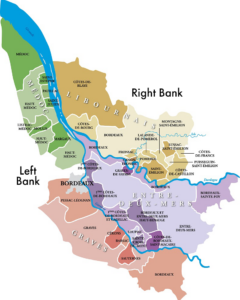

Bordeaux’s winemaking land tends to be separated into three large areas in relation to the Garonne and Dordogne rivers: the Right Bank, the Left Bank, and the ‘Entre-deux-Mers’. The latter being reputed more for its dry whites and sweet wines, it won’t feature in this article. Consider this article, then, to be a match between the Left and Right Banks, where we have a look at the differences in their soil, grape varieties, landscapes, and wine styles.

Two rivers

The landscape of Bordeaux is built around the Gironde estuary in the north and the Garonne and Dordogne rivers in the south. The region can thus be separated into three main areas: the Left Bank, south of the Garonne, the Right Bank, north of the Dordogne, and the ‘Entre-deux-Mers’ between the two. Since the latter doesn’t really fit into the classic profile of Bordeaux’s production – red cellaring wines made from a blend of varietals – it is considered another world from a wine point of view. So what are the specificities of these sub-regions?

Left Bank, the heart of Bordeaux’s classicism

- Gravel-rich soil

- Cabernet Sauvignon, the reigning grape

- Powerful wines apt for cellaring

- The Sauternes appellation

- Strong reputation for its top classifications

- Large estates that belong to groups and investors

The soil and climate

The Left Bank is comprised of three prestigious sub-regions: the Médoc (north of Bordeaux), Graves, and Sauternes (south of the city). The soils of the Médoc and Graves are varied and essentially made up of gravelly earth. An oceanic climate nurtures the vines, bringing warm summers and mild winters. We also find a certain amount of clay, sand, and limestone here, with a few areas blending clay with chalk.

The reds of the Left Bank

The main grape variety grown on the Left Bank is Cabernet Sauvignon, which brings tannins, strength, acidity, colour, and black fruit aromas to the wine. Merlot is also grown, a more delicate grape that confers a certain softness to the blend with its lovely aromatics and more gentle tannins. Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot can also be found on the Left Bank. In the Médoc and Graves sub-regions, Cabernet Sauvignon is the main varietal by far, topped up by Merlot, then potentially including small doses of Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc. These wines are apt for ageing, tannic and powerful, with a complexity to their aromas. As they age, they become more refined, developing a more delicate character. The wines of Médoc and Graves have excellent cellaring potential, ranging from 5 to 30 years depending on the cuvée and the vintage.

The whites of the Left Bank

The Left Bank is home to a precious gem of the white wine world: Sauternes. This is an area with a personality of its own thanks to its proximity to the Ciron, a stream that creates a microclimate favourable to the growth of botrytis, a fungus that allows noble rot to develop on the grape and make sweet wine. Only dessert wines fit into the Sauternes appellation criteria. Three varietals are grown here, Sémillon (the main grape variety), Sauvignon Blanc, and Muscadelle (often incorporated in minimal amounts). Liquid gold in a bottle, these wines are aromatically complex, carrying notes of candied and dried fruit, honey, spices, and flowers, and they have incredible aging capacity; exceptional cuvées can be kept in the cellar for up to 100 years! Dry white wines are also produced in Graves and Pessac-Léognan, fruity cuvées to which the Sauvignon brings citrus notes and a fine acidity. These wines evolve to develop a slightly rounder texture on the palate.

The renown of crowning classifications

The wines of the Left Bank enjoy the recognition of the finest Bordeaux classification: the famous 1855 ranking. This list was decreed by Napoleon III for the Paris Exhibition, and domains were chosen according to criteria of notoriety, beauty, and price. This only concerned châteaux on the Left Bank of the Garonne (essentially Médoc and Sauternes, with a single Pessac-Léognan, Château Haut-Brion). This is a classification that still stands today, with only two changes made since its 1855 release. There is also a classification for the dessert wines of Sauternes and Barsac, in which the only ‘premier cru supérieur’ is the famous Château Yquem.

The domains on the Left Bank tend to be much bigger than those on the Right (often around 100 hectares compared to an average of under 10 for the right), and a considerable number of these properties now belong to groups and investors. Of course, the more hectares of vineyard, the more wine produced, thus Left Bank wines tend to be less ‘rare’ than their right-sided counterparts.

The stars south of the Garonne include Château Lafite Rothschild, Château Latour, Château Mouton Rothschild, Château Margaux, Château Cos d’Estournel, Château Haut-Brion, Château Yquem, and Château Climens.

The Right Bank, a dynamic scene

- Varied soil, partly clay-based

- Merlot, the reigning grape

- Wines that are more supple, balanced, and accessible in their youth

- A dynamic sub-region in terms of growing methods and blending

- Smaller domains that belong to their winegrowers

The soil and climate

Now to the right bank which is north of the Dordogne river and comprises such winemaking areas as the Libournais (to the east), the Bourgeais (Bourg and Côte-de-Bourg) and the Blayais (Blaye and Côte-de-Blaye). The Libournais is undoubtedly the best-reputed area due to the various red AOC appellations held within its borders. These include Saint-Emilion, Saint-Emilion grand cru, Pomerol, Lalande de Pomerol, and Fronsac. The Bourgeais and Blayais areas produce more dry whites (fruity cuvées made from Sauvignon, Sémillon, and Muscadelle) as well as red wines. In these different zones, the soil is largely clay-rich, though also incorporates chalk, sand, and some gravel. The Libournais is a beautifully hilly and varied landscape. The climate there is temperate, allowing the Merlot grapes to mature nicely, this being a varietal that thrives best when planted in cool and humid soil.

Reds of the Right Bank

In Saint-Emilion and Pomerol, Merlot is almost exclusively in the wine crafted. It can be accompanied by Cabernet Franc (bringing balance with its notes of red fruit), and Cabernet Sauvignon (for body and strength). Certain other varietals can be found in very small amounts, such as Petit Verdot, Malbec, or Carménère. These are supple and fruity wines with gentle tannins. Whilst these, too, are wines to be aged, they are often accessible sooner than their neighbours on the Left Bank.

The Right Bank is home to smaller properties, and thus are largely still owned by winemakers and their families. Saint-Emilion also has its share of grand cru classifications, not quite as illustrious as the 1855 but still unquestionably interesting for wine lovers. The Saint Emilion grand cru list is revised every ten years, and in 2022 Château Figeac and Château Pavie emerged as stars of the Right Bank, being classed as grands crus classés A. On the other hand, Château Cheval Blanc, Château Ausone, Château Angélus, and Château La Gaffelière decided to remove themselves from contention.

Big names in the area include Petrus and Château l’Evangile, both in Pomerol. Given that these properties are smaller and still enjoy an excellent reputation, their bottles are subject to high demand, both in the primeurs campaign and at auction. For thoses that says that there is nothing new coming out of Bordeaux, they should take a look at the Right Bank’s wine where they will be surpised by the dynamic wines produced by some properties. Not as restricted by the structure as in some other appellations, these producers create wines that stand out for their blends and their use of organic and biodynamic methods. As you can see, the Right Bank has a slightly more malleable character, highlight by the fact that Château de Valandraud is a premier grand cru classé but it was once considered a “vin de garage”.

This is by no means a comprehensive list of differences between the Right and Left Banks, but hopefully it has given you an idea of their distinguishing features, both nuanced and excellent in their own way.