The word mineral has become commonplace in wine-tasting jargon recently. Unfortunately, it’s used so frequently that it’s difficult to understand exactly what it actually refers to in a wine. All the same, let’s sketch out a few ideas…

Whenever someone mentions floral aromas or a fruity flavour when tasting a wine, everyone pretty much immediately understands what they are referring to. Even if each individual, with their own particular benchmarks, might smell peony where others might imagine rose, or be struck by aromas of redcurrant where others might be hit by notes of raspberries. No matter what, a floral aroma remains floral and a fruity flavour remains fruity. However, when it comes to mineral, things are much more complicated…

As a result of being used willy-nilly, the meaning of this word has become somewhat blurred and has become a pseudo-savvy way of saying that mineral wine equals good wine. Whether due to a lack of experience or a lack of analysis, it’s convenient to say ‘mineral’ when you’re not sure exactly what to say to explain why you think a wine is very good. Ironically, it’s actually quite true!

Although it is difficult and depends – as all sensations experienced when tasting a wine – on the taster’s own perceptions of the world of smells and aromas, we can try to define what a majority accepts as minerality and clearly state what minerality is not!

So what s minerality in wine?

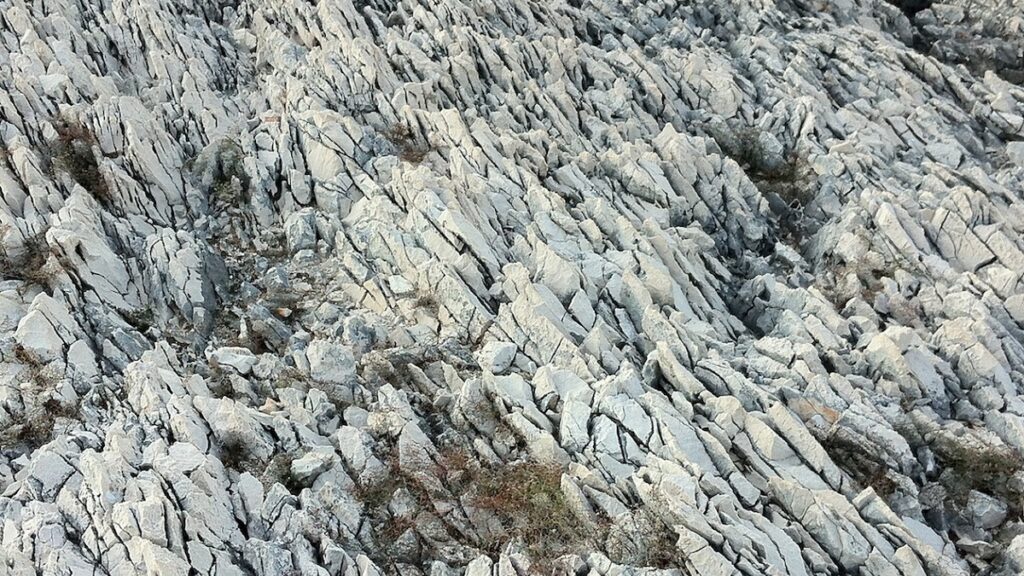

To the majority of discerning connoisseurs, in the first instance, minerality evokes a range of aromas associated with the soil: the smell of limestone, flint, earth, shale, graphite, wet stones, sun-kissed stones, and so on.

Next, on the palate, it initially seems associated with a sense of touch that’s quite difficult to describe, and which, for the most observant of tasters, has to do with a feeling of ‘vibration’ or ‘dynamism’. And, on the finish, the minerality is clearly associated with a slightly salty flavour, which in turn triggers a burst of saliva to flow back into the mouth. ‘Mineral’ and ‘salivating’ are generally completely intertwined.

On the other hand, don’t mistake minerality for acidity, a common misconception among inexperienced tasters (and even among more experienced ones). In fact, this probably explains why most of them speak of minerality more often when referring to white wines than red wines, which is a mistake. A fine acidity, well integrated into the wine’s substance, probably contributes to that well-known sensation of ‘vibrancy’ or ‘dynamism’ on the palate, but it does not fully sum it up. Minerality is a sensation sustained by many other factors. With some white wines, minerality is often confused with rather strong sulphur aromas, which, combined with a slightly high acidity, can be misleading.

Last but not least, it is important to know that the taste of a fruit – an apple or a grape – is directly influenced by the nature of the soil from which it originates. But let’s be clear about one thing, this is only really true if the grapes are produced and vinified as naturally as possible. You don’t need to be an expert in agronomy to appreciate that a wine produced from grapes grown in soil that has been smothered in chemicals and vinified with impressive quantities of (authorised) oenological products will not express the soil in which it was grown. So to talk of minerality for wines produced in terroirs that have been obscured or ‘filtered’ by a range of excessive practices in the vineyard or cellar is absolute nonsense! However, when a wine is produced more or less ‘cleanly’, it is really interesting to try and appreciate the differences between, for example, a wine produced on very chalky soils and another that comes from marl or clay soils. As an example, have fun tasting a Vouvray such as François Chidaine’s cuvée Les Argiles, which reflects the nature of its soil in its very name (argiles means clays in French), and a Saumur such as Thierry Germain’s Cuvée Insolite from Domaine des Roches Neuves produced on a very chalky tuffeau limestone soil. Both are extremely mineral wines, but their mouthfeel is completely different. The Saumur is light and crystalline, while the Vouvray is broader and ‘heavier’, reflecting the soils from which these two wines originate.

Let’s finish by mentioning that, more than any other olfactory or gustatory perception, the concept of minerality is highly subjective and has been the subject of passionate and often unresolved debates in wine-tasting circles for some time now. Nevertheless, in one way or another, ‘true’ minerality is indeed a reflection of a good, even great wine. Without the depth of minerality that links it to the soil, a wine that offers only fruit, acidity or richness can probably be a good wine, but it will never be a great one…

All our wine currently for sale on iDealwine