A few months ago, we began a collaboration with the excellent Sicilian domain Frank Cornelissen. These wines have really blown us away, so we wanted to find out a bit more about how they are made and the man who makes them! Here’s an interview we conducted with Frank.

How did you start your career in wine and how did you train for it?

I didn’t begin with technical training; it was my passion for wine that guided me. For me wine is a product closely linked to spirituality and terroir. When you taste a wine, you should be able to sense its roots, where it comes from. Terroir comes first, then man, then technique.

The specificity of terroir is precisely the reason I chose not to learn about wine in an overly-structured way, since the work of a particular producer on their particular land is relative. In another place, in another climate, the wine is made differently, so everything you’ve learnt is irrelevant. The only thing you can really learn is the practical side of managing a viticultural domain: how much to produce to make it profitable, how to organise a cellar, a team. I also think that learning from someone else means you lack a personal vision of wine.

Why did you choose Etna, a terroir that was largely unknown at the time?

Because it’s a really fine terroir! The combination of the geology, the climate, and the varietal makes it up, and fine terroirs are where unique wines can be crafted. But there are not many fine terroirs in the world. The climate has to be adapted to viticulture, of course, so it can’t be too humid; this already excludes about ¾ of the earth’s land. Fine terroirs are those that can produce wines with personality, offering real finesse and depth, and maybe only 1% of winegrowing areas possess this kind of profile. In this sense, Etna didn’t exist back then. Personally, I don’t like to pursue what has already been done. We know what the finest Bordeaux is like, same goes for Burgundy. Monks worked for centuries on perfecting the cru and classification systems to an art, and the grands crus really have superior finesse and personality. Burgundy is exemplary in this respect.

There was already a classification system on Etna when I arrived, based on the vines expressing a certain style and a certain taste. I didn’t know this before, so I learnt about it in 1999 from the people already here. This got me thinking, and I started to compare the wine made by local producers. They all followed the same methods, but their wines were very different depending on the terroir. Tasting in this way gave me a good idea of the grape quality in different places. Etna had all the right ingredients, the potential to produce fine wine (climate, well-adapted varietal, special geology). After 5-10 years, this potential was confirmed, especially in the northern valley for the red wines. It’s a bit like in the Côte de Nuits, wines that taste totally different compared to their surrounding vineyards.

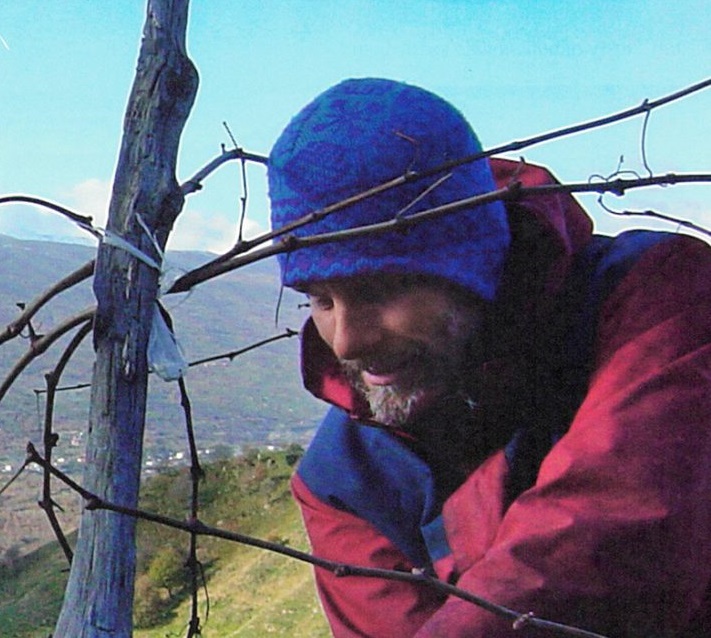

How difficult is it to work with a terroir with such steep slopes at such altitude?

I’m often asked this question, but honestly, it’s not that difficult. My highest vines are at 1,000m, so the lowest third of Etna. You definitely need to use different equipment but its viticulture like any other. We have had problems with our equipment breaking because of the rocks, so we’ve had to invest in more solid and more expensive materials. This is quite costly but other than that, it’s alright.

The biggest problem we have is actually the risk of drought. The soil holds onto very little water here, so it can be quite precarious for the younger vines that we’ve planted more recently. However, once the vines have pushed their roots deep enough, they are strong enough to bear the dry, summer climate, and if we treat them well, they can last for a hundred years.

How do you work in the vineyard?

My work is organic. I don’t plough the soil much anymore, a carefully considered choice that’s hard to put into practice. We can do this on the more sloped parcels, but at the risk of grass and other plants dominating the delicate plant life. It’s easier to avoid ploughing the soil in balanced climates with more water.

We’re living in a good time for organics, it’s really encouraging, more and more people are aware of it, the world is paying attention to it. We’re still often putting copper in the soil and there’s more discussion around that, it’s an important topic, we’d like to stop using it altogether. This is a period of awareness and active research into all these subjects.

Are you interested in biodynamics?

I don’t practice biodynamics on my domain and I don’t wish to. I like how careful its methods are, particularly in its sensitivity to the lunar calendar; this is a technique that I try to apply in the winery. But with a vineyard of 10 hectares you just can’t do it. We usually have two and a half days to treat all the vines so it’s not possible. I have tried but I had to stop. Domains like Leroy and Leflaive have the people power and the right materials, but I have doubts about other domains. We would need a tractor, for example. To be truly biodynamic is hard and very expensive. We could maybe get to that stage, but beyond the practical concerns it’s not actually a step I want to take. For me, biodynamics is an example of humankind looking to intervene too much, altering the natural course of nature and its balances. Biodynamic treatments, for example, are about altering the cosmic and energetic path of the vine, accelerating its metabolism. This is an intervention into the soul of the vineyard, and that’s hard for me to accept, I’m not its creator.

I think a lot about questions such as these, and if we don’t have the sensitivity of someone like Nicolas Joly, for example, it’s actually possible to damage the vines by using too much of a given treatment. I made this mistake in 2002 and lost some leaves. After that, I reflected on the practice and began to question the legitimacy of biodynamics: who am I to change the course of the year? This would be like making “cosmically modified” wine. By this logic, it’s not so different from chemical alterations.

Why do you use the pied de cuve technique?

[The pied de cuve technique involves fermenting a very small percentage of the harvest to instigate the work of indigenous yeasts.]

This is a technique I learnt in France, and it allows you to better guide the vinification process and avoid making a faulty wine. It means we can make good yeasts for the year; we start with 20-30kg of grapes and if they go off course, we can throw them out and start again. It’s a very artisanal way of making wine, and we choose the pied de cuve grapes very carefully. It’s quite a slow process that later picks up momentum.

How do you explain the popularity of your wines in recent years?

I think this success is a result of a few different things: firstly, we live in a small and well-connected world, we’re social beings and we like to share, to exchange; this is the essence of our existence. Being successful is often due to people seeing a kind of sincerity in what you do. But if you want to sell across the world, you have to have enough produce, though not too much or you risk losing all your energy. I began with 1,000 bottles and now I make 140,000. I still do all my invoices myself, though, and I know my clients really well; I like to keep in touch with them. If someone else were doing it instead of me, the domain would have a different feel to it. I like both sides: the work in the vineyard and the winery, as well as the client relations. People are very sensitive to things like this. Finally, I am truly passionate about wine, so I’m always seeking to improve my produce. Sometimes I’ll go back to the winery at 3am because I’ve had a new idea! And when an artisan is passionate about their vocation, you can tell. I’m not perfect, of course I make mistakes, but the people who enjoy my wine have an affinity with the philosophy of the domain. That’s a very important thing.